A Language in Hiding

For many fluent Nuu-chah-nulth speakers, their language was something they kept hidden within themselves to safeguard their loved ones.

“Because the Catholic Church tried to beat it out of us, my own way of protecting my kids was not to teach them our language,” said Moses Martin, Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation’s elected chief. “I never taught any of them.”

As a result, only 108 fluent speakers remain within the 12 Nuu-chah-nulth nations surveyed in the 2018 Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages.

B.C. accounts for around 60 per cent of the First Nations languages in Canada. There are currently 34 Indigenous languages within the province. Of those, three per cent of the reported First Nations population are fluent.

In 2003, FirstVoices was developed by the First People’s Cultural Council (FPCC) to support Indigenous people engage in language archiving, teaching and cultural revitalization. The web-based suite of tools allows nations to create their own language sites by uploading words, phrases, songs and stories as audio and video files. Now, 32 out of the 34 First Nation languages in B.C. can be found on the platform.

“It’s simply imperative to reconciliation in our country that we provide resources and opportunities for [First Nations communities] to have self-determined language projects,” said Kyra Fortier, language technology programs coordinator for the First Peoples’ Cultural Council.

Examples of self-determined language programs can be found throughout many Nuu-chah-nulth nations.

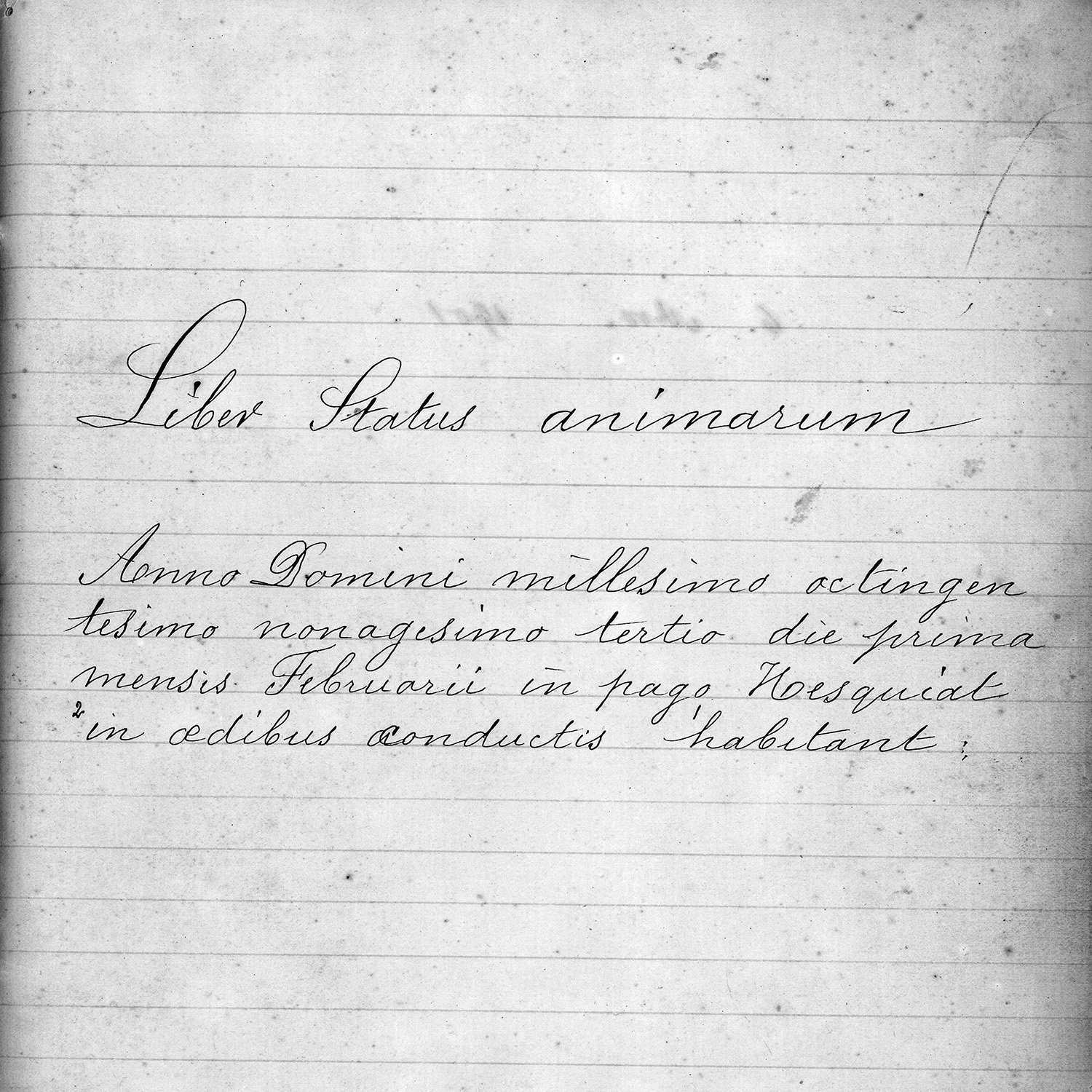

As part of the Hesquiaht Language Program, nine of the nation’s 12 fluent elders every week. In June, they began teaching an online language program that has attracted nearly 100 students, ranging from Vancouver Island to California and beyond.

“The language is coming back from the effort of the group,” said Layla Rorick, who coordinates the program. “Everyone remembers different things and [collectively], they put a more together a more complete picture of the use of our language. Nobody is bringing the language back themselves as an individual – it’s the whole group. All of our fluent speakers are bringing it back for people.”

Frances Tate dons a traditional shawl.

Helen Dick grew up in a fluent speaking home and continues to speak her language fluently. "I used to hear my mom tell us, 'just be who you are. Don't let people try to change who you are or what you are. You be you.' So that's how I've tried to live my life," said the Tseshaht elder.

Charles John Seghers, a Belgian clergyman and missionary bishop, drew this map in 1877 after four years of living on Vancouver Island. The map's wording transitions between Dutch, English and his approximation of First Nations dialects.

Benson Nookemis holds a traditional mask.

Barney Williams is one of the remaining fluent speakers within the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation. He attributes the decline of fluent speakers to the residential schools' "shame-based way of teaching." "We carried that trauma through life," he said. "We were always afraid that if we talked, we'd punished, or that somebody would laugh [at us]."

Frances Tate was born and raised near Nitinaht Lake. The 77-year-old was raised in a fluent household but lost much of her language while attending residential school. In her late-50's, she began taking language classes through the Ditidaht Community School. She now identifies as semi-fluent. Along with other elders, she helps children with the pronunciation of words and phrases at the school. "Some of our elders say that [our language] is very close to being extinct – it’s very close to being gone," said the Ditidaht elder. "But we have young people that are teaching now, and they’re very strong. [I'm] encouraged by them."

Tyrone Marshall and Christine Hintz hang post-it notes of Nuu-chah-nulth words inside their home in Port Alberni to apply the language in their daily lives. "It’s like a gateway to our culture," said Marshall. "It’s so important to pay homage to the people before us who – with no resources, with no money and with no internet – made sure there were recordings out there, made sure we understood what 'heshook-ish tsawalk' means."

![Levi Martin wears a shawl that he dons while delivering ceremonies on big occasions.

"When I have to speak in public, I the ability to connect with the ancestors," he said. "I will be their voice [to] channel their message."](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64441c4942715114326d1a95/27f61b08-04b0-4456-969d-d73a2fdb46c1/Elders9.jpg)

Levi Martin wears a shawl that he dons while delivering ceremonies on big occasions. "When I have to speak in public, I the ability to connect with the ancestors," he said. "I will be their voice [to] channel their message."

Moses Martin holds his drum.

Moses Martin, the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation elected chief, is one of the remaining fluent speakers within his nation. The 79-year-old said he is helping to generate audio recordings "for future generations."

Just 108 fluent Nuu-chah-nulth speakers were identified in an 2018 survey, but interest in the language is clearly emerging from the shadows.

During Gisele Martin's mentor-apprentice program with Levi Martin, she labeled everything in her house with the correlating Nuu-chah-nulth words. "Every cupboard, every counter, the floor – everything," she said. It prompted a discussion that led them to determine that language needed to be more visible throughout the communities of Ty-Histanis and Esowista. The pair set out to write the word "tuumsac," which translates to "garbage," on the community dumpsters with white paint. "Make it useful in your daily life," said Gisele. "Find ways to put the words everywhere."

An old polaroid (top left) of the boat that Pat Charleson hand-built hangs on a wall inside his home in Port Alberni. The 90-year-old constructed the 42-foot troller named "Eileen C" in the late-40's without using any power tools.

Benson Nookemis did not know a word of English when he was sent to the Alberni Indian Residential School. His mother hardly knew any English so he was raised speaking the Huu-ay-aht dialect, which he continues to speak today. The 85-year-old said he can count the remaining fluent speakers within his community on one hand. "It makes me feel sad," he said. "We're losing our language. Every time there's an elder that passes away up-and-down the coast, it's another person that we've lost that knew how to speak their own language."

A photograph of Helen Dick's parents, John and Bessie, hangs on a wall inside her home in Port Alberni. It was taken on their wedding day. When Helen was growing up, her mother used to say, "if someone wants to learn about their culture, their language or their territories, you need to help teach them. Give them your knowledge. Don't ever tell them, 'that's not right – you said it wrong, because they might just give up.'"

![Levi Martin wears a shawl that he dons while delivering ceremonies on big occasions.

"When I have to speak in public, I the ability to connect with the ancestors," he said. "I will be their voice [to] channel their message."](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64441c4942715114326d1a95/b3623008-86ee-45fd-9aac-a30eade69eed/Elders17.jpg)

Levi Martin wears a shawl that he dons while delivering ceremonies on big occasions. "When I have to speak in public, I the ability to connect with the ancestors," he said. "I will be their voice [to] channel their message."